Main Second Level Navigation

Breadcrumbs

- Home

- About Us

- Our History

- Early History of Ophthalmology in Toronto

- Abner Mulholland Rosebrugh

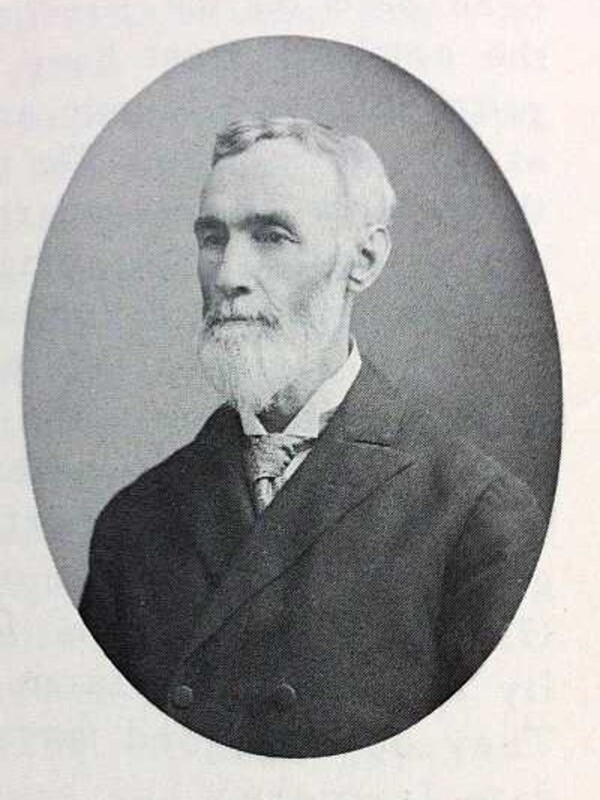

Abner Mulholland Rosebrugh (1835-1914)

Abner Mulholland Rosebrugh is referred to as the father of ophthalmology in Toronto, as he was the first Toronto physician to limit his practice to eye and ear diseases. He was born into a farm family in 1835 in Dumfries Township near Galt, Ontario. He graduated with an MD from the Rolph School of Medicine in Toronto in 1859 and started a general practice in Preston, Ontario. He then traveled to New York and London for post-graduate medical training and returned to practice in Toronto in 1863. He opened an Eye and Ear Infirmary on Adelaide Street West in Toronto where he served the poor over the next several years.

Rosebrugh was interested in inventions in and outside of ophthalmology. In 1864, he designed the first ophthalmoscope with which one could photograph the fundus of a living eye. He tested the device on animal subjects and described at length its design, its optical principles and his experiments:

"As yet I have not attempted a photograph of the retina of the human eye, but have confined my experiments to the lower animals, and I have used solar light only in order to shorten the time as much as possible . . . In photographing the eye of a cat, I found it necessary to put it under the influence of chloroform, but the image of the optic nerve, vessels, etc., upon the ground glass is so very bright and clear that I do not doubt if the most sensitive process be adopted, the impression could be taken instantaneously, thus rendering anaesthesia unnecessary."

Rosebrugh worked with the optician and instrument maker Charles Potter (1831-1899) at 20 King Street East, and made a photographic ophthalmoscope available for 10 dollars. Rosebrugh made a plea to his colleagues to adopt the instrument as freely as they would a stethoscope. An editorial in the 1864 Buffalo Medical and Surgical Journal praises Rosebrugh's instrument in its ability to both be adopted as a camera obscura, where the image of the fundus is projected, and to make photographs using prepared photographic plates. They conclude that it will "aid in banishing from ophthalmic nomenclature the indefinite term of amaurosis, where, as Walther observed, 'the patient sees nothing, and the surgeon likewise – nothing.'"

23 years later Rosebrugh published an Original Communication in The Canadian Practitioner describing his experiences using the photographic ophthalmoscope on humans and the mechanism of his device, with a detailed diagram of the camera tube.

A reference to a Toronto physician's creation of the first fundus camera is recognized in the American Academy of Ophthalmology's commissioned book, The History of Ophthalmology, though Rosebrugh's name is not acknowledged.

Rosebrugh and Potter worked together on several other inventions. In an advertisement in the December 1887 edition of The Canadian Practitioner, Rosebrugh promotes a medical battery, used in the treatment of nervous and chronic pain disorders, named "The Rosebrugh Improved Constant Current" available for purchase through Charles Potter.

More notably, Rosebrugh invented and patented a method for transmitting telephonic and telegraphic messages on the same wire, called duplex telephony. In January 1887 he described duplex telephony at length to the members of the Canadian Institute. He sold the patent rights to the Bell Telephone Company of Canada. Rosebrugh was a close friend of Graham Bell and helped him in the development of the telephone. Rosebrugh held six patents relating to the improvement of telephones and is said to have had the first telephone in Toronto.

Rosebrugh contributed greatly to the ophthalmic education of medical students at both the Toronto School of Medicine and the medical department of Victoria University. A series of his lectures on diseases of the eye were subsequently published in the Canadian Medical Journal of Montreal in 1866 for the benefit of physicians practicing throughout Canada. In his series he covered the principles and management of "optical defects of the eye" and the treatment of hypermetropia, myopia and presbyopia with lenses. In his lecture he states:

"There is an optical defect of the eye that is occasionally met with called astigmatism in which the horizontal and vertical lines are not brought to a focus at the same distance behind the lens. I have seen but one case."

He also described "convergent strabismus" and stated the treatment was with convex lenses.

Rosebrugh understood and taught the optics of refraction and accommodation well before it was common practice. His lecture series occurred only one year after the first major textbook of clinical optics by Franciscus Cornelis Donders (1818-1889) was published in 1864.

Outside of his medical and scientific endeavours, Rosebrugh was dedicated to social welfare. In 1890 he was appointed to a Royal Commission on the Prison and Reformatory System of Ontario. The commission revealed that poor and neglected children were frequently involved in the reformatory system. They recommended an association be established to look after the needs of homeless and vulnerable children in Toronto. This ultimately led to the creation of the Toronto Children's Aid Society.

Rosebrugh died in Toronto aged 79 in 1914.